The Science of Getting Started: Why Motivation Fails You

As we all know, starting a new task can often feel like the hardest part. Why is this? It all comes down to motivation, but that’s still a bit of a vague answer. When I say "motivation," we might all have different images in mind. For this discussion, we’ll work with a definition I’m most familiar with: From the perspective of behavioral neuroscience, motivation can be classified as the energizing of behavior in pursuit of a goal (Simpson, 2016). In other words, it’s that gut urge you feel to initiate something you’ve been putting off.

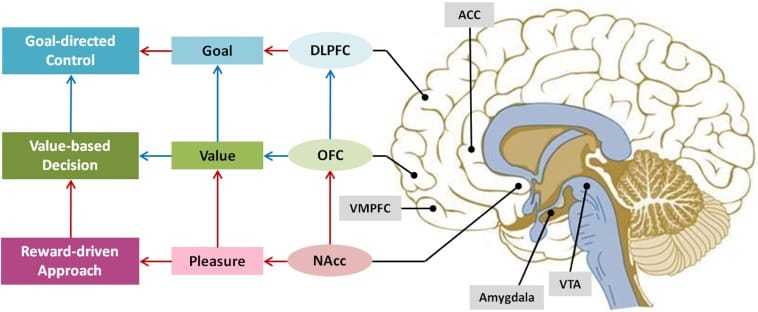

So, what exactly is that feeling? To understand it, we need to take a look at the biological mechanisms happening behind the scenes. One of, if not the most important, factors in initiating motivation is reward. However, rewards alone aren't the whole picture—there’s a fine balancing act between the effort required to obtain the reward and the perceived value of that reward itself. While I won’t dive too deep into the complex mechanisms of motivation here, there are a few key ideas that can help clarify the process. First and foremost, motivation is tightly linked to the dopamine pathways in the brain’s reward system. This system works in tandem with several other neural pathways that involve anticipating the reward, associating it with certain behaviors, planning to achieve the reward, encoding the reward’s value, and continuously updating its relative value (Kim, 2013).

For our purposes, the key element we’re focusing on is the initiation of motivation—specifically, the starting point of a task. That first step is what we’re aiming to optimize, the spark that gets the engine running toward accomplishing our goals.

The Biology of Motivation: What Fuels That First Step?

To get things moving, the first thing you need is a goal. But not just any goal—a balanced goal. This means that the goal must take into account both the effort required to achieve it and the value of the reward upon completion. Now, this reward can be virtually anything, as studies have shown that both social and physical rewards activate similar brain regions, suggesting that the brain treats them similarly in terms of motivation and reinforcement. Whether your reward is something tangible, like money, or something more abstract, like praise, the brain will respond to both if they are perceived as being of similar value. This is key—perception of value matters.

The Effort-Reward Balance: Why It’s Crucial

Now, let’s talk about the effort required to reach our goal, because this is where it gets interesting. As we mentioned earlier, a large part of our motivational system involves weighing the work versus the reward. Our biology inherently resists the idea of expending effort for a reward that doesn’t seem worth it. It doesn’t take much explanation to know that if the reward for an hour of hard labor is just a few cents, motivation will be hard to come by.

What’s even more fascinating, however, is how this subconscious weighing of effort happens all the time. On a neural level, your brain is continuously calculating the relative effort required for a task and comparing it to the expected reward. If there’s too much effort and too little reward, the brain may simply not activate the motivation to start the task. This is why you should always ensure that the goal you have in mind is reasonably balanced—if the effort is too high for the reward, your brain will work against you.

But here’s an important caveat: setting goals that are too easy can also backfire. While a seemingly achievable goal might seem motivating at first, research has shown that overly simplistic goals can actually lower engagement and the quality of work. A more challenging goal has been shown to result in higher motivation and a greater quality of work, as it pushes the brain into a more focused and effort-driven state (Locke & Latham, 2002).

Summary

To summarize, the process of generating motivation and getting started on a task is influenced by both the value of the reward and the effort required to obtain it. The brain’s reward system, primarily driven by dopamine, continuously weighs the value of the reward against the effort needed. The key to initiating motivation is ensuring that your goal is perceived as both challenging yet attainable, with a reward that justifies the effort. Too easy of a goal might fail to activate sufficient motivation, while an overly difficult one might lead to frustration.

In our next post, which will be the second part of this series on motivation, we'll explore strategies for maintaining motivation over the long term, diving into practical tips to keep your momentum going once you’ve taken that first step.

Works Cited:

“E. T. Berkman and M. D. Lieberman, "Approaching the Bad and Avoiding the Good: Lateral Prefrontal Cortical Asymmetry Distinguishes between Action and Valence," in Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1970-1979, Sept. 2010, doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21317.”

Berkman ET. The Neuroscience of Goals and Behavior Change. Consult Psychol J. 2018 Mar;70(1):28-44. doi: 10.1037/cpb0000094. PMID: 29551879; PMCID: PMC5854216.

Kim SI. Neuroscientific model of motivational process. Front Psychol. 2013 Mar 4;4:98. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00098. PMID: 23459598; PMCID: PMC3586760.

Becker, L. J. (1978). Joint effect of feedback and goal setting on performance: A field study of residential energy conservation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(4), 428–433.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705